Trebinje

Trebinje is a small town, lost in the dry mountains of the southern edge of Herzegovina. Hidden in a deep valley, it may resemble end of the world, when entering it. But I knew that there are some experienced producers of quality wine there and my trip to this town did not disappoint me at all. More: I could not stop marveling over the assets Trebinje enjoys.

As lost as it may appear, it is not difficult to reach – situated in the corner between Croatia and Montenegro. It is all about a short drive from Dubrovnik or Herceg Novi, both highly touristic spots of the eastern Adriatic coast. But you need a car… and I don’t have any. I do not drive. Americans will feel shocked, Europeans less surprised. Using public transportation, I made quite a nice circle to reach the town. I came from Montenegro, via Dubrovnik in Croatia, and went to Mostar – to see one of the most famous bridges in the world, and to spend night before continuation of the journey. I could stay in Dubrovnik too, but young traveller’s budget is not adapted to this terrifyingly commercialized, UNESCO-protected Disneyland.

Trebinje

Mostar is the historical capital of Herzegovina, inhabited mostly by Catholic Croatians and Muslim Bosnians, each group preferring to stay on its side of Neretva river. The 16th century bridge is what connects both communities both virtually and symbolically. Destroyed during the war in Bosnia, it was rebuilt in its original form soon after. On the Muslim side, just a few meters from the bridge, there is a Serbian café, which I discovered on the very first evening. It was a prelude to my trip to Trebinje. The café offered exclusively wines from the Monastery of Tvrdoš – one of my destinations. So – of course – I had a glass. To be precise, it was a glass of the monastery’s Cabernet, called “Hum,” called after the medieval principality in this region. It was a pleasantly cool evening, with Neretva resoundingly weaving its way through the rocks of its bed. The 2007 “Hum”, kept for two years in French oak, had those minerals giving it a smell of blood. Subtle spices, forest fruits and a bitter herbal notes were developing in the contact with air.

Tvrdoš monastery, wines

Tvrdoš monastery, vineyards

It was the evening of the next day, when I arrived in Trebinje. The town is situated in Republika Srpska, which should not be confused with Republic of Serbia. The former one is a part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, within its patchwork-like postwar political and administrative system. Bosnian people owe this mess to the Dayton Agreement, which should bring peace but also caught them into a trap of dysfunctional system that impedes economic development. In fact, during the time I stayed there, in many Bosnian cities students were protesting against this inconvenient political construct offering them no future.

Staying in the centrally situated hotel “Platani,” I had the small historical center around me, and the old famous plane trees above, after which the hotel was named. Tired, I went to the first nicely looking restaurant: “Tarana”. Over there I ordered 0,5 liter of their house wine and a plate with Herzegovinian prosciutto ham (Serbian: pršuta) and hard cheese marinated in olive oil (sir iz ulja). This is one of the places where “vino de casa” is not worse than any other one sold by bottle – their white is Žilavka from Anđelić, another great producer I was going to visit in Trebinje. This was divine food and, as I discovered later, only a modest beginning. The aforementioned Žilavka got a medal from the Decanter: a dry but fruity wine, of a golden-green color, elegant in its structure and so different from many rich, strong whites of the Mediterranean climate.

The next day was a Sunday and I took a cab to the Monastery of Tvrdoš, which is – I guess – not more than 5 km from the town center. The typically small Orthodox church is from the very beginning of the 16th century, constructed on the ruins of older temples, the earliest one from the 4th century. But the big part of the winery is rather new. The monastery has a long wine making traditions, which suffered however from the Turkish, and later from the two World Wars, the communism, and the war in Yugoslavia. As a matter of fact, they started their quality wine production only in the early 2000s. In the cellars, I was warmly received and the long talk, I enjoyed with one of the cellar workers, was only shortly disturbed by groups of tourists coming to visit the church and have a tasting of wines and spirits.

The monastery has seven wine and three spirit labels, the spirits produced from grapes too. As every respectful producer of the region, they have their Žilavka, an autochthonous variety, appreciated much by the Austrian-Hungarian emperors, who sourced it from a Hungarian producer in Lastva, a village to the south of Trebinje. Tvrdoš’ Žilavka was a beautifully balanced white, mineralic and with refreshing acidity. The strong sun, additionally reflected by limestone, makes the wines strong though, this one containing 13,7% of alcohol. The vines grow on stony, dry and poor soil with their roots reaching deep into the rock. It is not unlikely that the name could be traced from the word “žilavost,” meaning tenacity and strength. I’ve heard once that genetically Žilavka is not that far from Riesling and indeed whoever loves German and Austrian Rieslings most probably will appreciate tenacious whites from Herzegovina too. But also the Chardonnay “Oros” (Greek for mount) proved to be an elegant wine – with its fruity and honey notes and spiciness. My first red was Merlot, blended from two vintages: 2008 and 2009. It’s called “Izba” – an old Slavic word for cellar or pit-dwelling. In medieval times, the monks kept their wines in such an izba. This light plumy wine was beautifully rounded by oak, its exciting herbal notes (mint and sage?) underlined. Good start before the 2007 Cabernet “Hum,” which I mentioned before. There are few Cabs that I don’t find tasting like all others, myself being only a moderate fan of this variety. In this one, I love its fresh acidity, forest berries – first of all European blueberries (bilberries), and bitter herbal accents. But Tvrdoš’ champion is Vranac, my bottle being from 2010. The harshness and fruitiness are mixed in a lovely tradition of this part of the world. Vranac gives wild and strong wines, acidic and heavy, particularly in its most prominent terroirs around Lake Skadar in Montenegro. In Serbia and Herzegovina, producers try to make it rather modern, tame it and reach this way more elegant creations. This one is even sweetish in aftertaste, revealing caramel-like, cherry and dried cranberry notes. The monks manage to produce even a quality sweet red – a drinkable and virtuous sacramental Cabernet Sauvignon!

For a late lunch, I went to a restaurant that was recommended by virtually everyone I asked for a good place to eat. I won’t keep its name secret, although I maybe should. Still, I’m aware that the mountains of Herzegovina will stay a barrier high enough to quick and exaggerated commercialization, and thus tradition destruction (see: Dubrovnik). In the “Konoba Studenac,” I had fresh trout, the restaurant being situated at the Trebišnjica river. The owner raises fish also in the pool in the middle of the garden, with fresh water from Trebišnjica. I took also grilled red bell peppers, which are marinated with garlic and herbs – an all-Balkan tradition, and French fries – freshly done, not frozen, from a bag, as it sometimes happens. The wine I had was again Žilavka from Anđelić’s cellars. The river simmered, the wine simmered – I felt like a dessert, and it had to be happiness, because otherwise I was full after all that fish they served me. Dessert was very Balkan – a huge portion (because here small portions are almost offending!) of tulumbe pastries. The incredible part of the meal was not only quality, but also the price – I paid for all of that not more than $15!

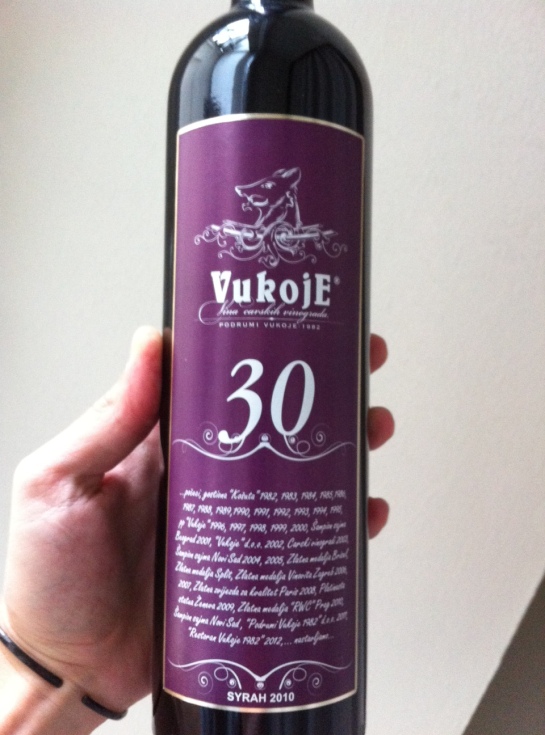

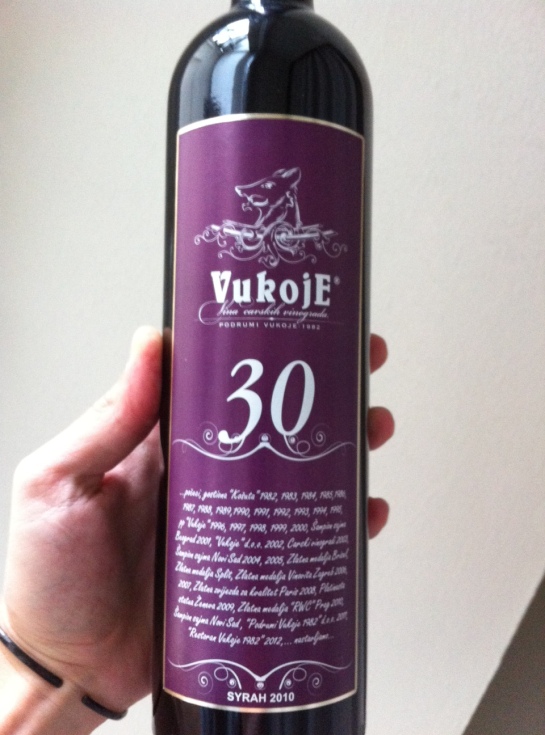

On Monday, I started my week in the Vukoje winery, which is considered one of the best wineries in the whole Southeastern Europe, their tasting room wallpapered with medals and prizes. The producer has even more labels than Tvrdoš, so this time I tried only some wines, selected by my host. We started with the 2007 “Zlatna Vukoje Selekcija Bijela” – a product from selection of best Chardonnay (60%) and Žilavka (40%) grapes. They call this cuvee a golden selection and indeed there is the sun and aromatic herbs inside, so typical for the local whites. The wine is oaked for 12 months, and enchants drinker with notes of almond, dry figs and quince. The second glass was filled with 2007 Cabernet “Tribunia.” Tribunia is an ancient name of Trebinje and designates a varietal wine series from international grapes. This elegant Cab seduced me by its forest fruit and tobacco (?) notes. Its sweet and tart notes as well as tannins are well balanced. Oak was used only to its advantage. It has a potential for aging to satisfy with increased complexity of its fruity bouquet. Further, we compared Vranac “Rezerva” from 2006 and 2008. The former one is not available in the market anymore – what a pity! Its smell – alluring honey, sour cherry, chocolate and tobacco notes, becomes richer every time your nose is diving into the glass… pepper, cinnamon… there was the original wildness of Vranac visible, reemerging with age. The younger Vranac was less acidic, with notes underlined by oak more assertive. Its original wildness was tamed and hasn’t reappeared yet. There was something like honey acidity – kind of modern character but with traditions! Personally, I preferred the older one, but I strongly believe in the potential of the young.

Vukoje cellars

In the afternoon, I went to Vukoje’s restaurant, kept much in the Slow Food spirit. They source the majority of their ingredients from the local organic producers, offering this way exceptional olive oil, cheese or ham. My plan was to try here some dish containing raštan – a sort of cabbage used in the regional cuisine. However, I begun with a „Herzegovinian plate” being a mix of several delicious starters, for example, hard goat cheese aged in olive oil, two or three kinds of pršuta (Balkan type of prosciutto ham), cheese and herb pita (more like burek than pita bread from the Middle East). All this was served with freshly baked bread. My aperitivo was a glass of travarica – grape rakija with several herbs, rosemary being the most important one. The main dish – chicken breast fillet, stuffed with collard leaves (Serbian: raštan, Croatian: raštika), with slices of ham and in creamy mushroom sauce – was served with wine: Vukoje’s Žilavka. This was an awesome combination, although afterwards I came to the conclusion that a glass of Pinot Noir would be even a better pick. Then a waiter brought a glass of bitter on house – a mix of almost 60 herbs pleased my already satisfied stomach. No problems with digestion were even thinkable! The owner gave me also a bottle of their Syrah – a new label created for the 30th anniversary of the winery and restaurant, celebrated last year. Later I spent with this wine my last evening in Trebinje, reaching the state of serenity, so characteristic for the town. The Syrah proved to be a fruity wine, with intense aroma of blackberries and black currant, black also by color.

Restaurant Vukoje, antipasti (I took the picture too late)

From the restaurant I took a taxi to the Anđelić’s cellars. I was lucky since I arrived in the moment when they were about to close. Here, like in other two wineries, they were expanding their production and facilities for visitors – an impressive growth in this hardly known part of Europe! Still, every year Trebinje has more visitors. The producer told me that just in the last few weeks he had plenty of tourists from Norway, Poland, Russia, and Sweden.

Since I knew their Žilavka, I started with Chardonnay “Žirado,” and this was a shock. This aromatic, buttery but fresh wine, with a scent of ripe apple, was dry but tasted like semi-sweet, and what’s more, it tasted like “Jagoda” from the winery of Botunjac, in Serbia. However, Jagoda is a unique variety in the Župa region, so how comes that Chardonnay gives a wine with impressively similar aroma and character? Funnily, the producer said that it perfectly goes with štrudla cake. So does the “Jagoda!” Confused, I grabbed the glass of Rosé from Merlot, called “Lira.” It had an interesting copper color, like diluted port wine. The smell was intense, kind of cooked strawberry. Astonishingly, this was the strongest wine of the cellar: 14,5% of alcohol. The first red was a cuvee of Vranac, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot called “Tribun” – a very subtle and balanced wine of beautiful color. Pure Vranac, also from 2009, had of course more temperament; yet, it had a delicate aroma of bilberry and something earthy. They have also “Mičevac” – a barrique version of “Tribun.” Unfortunately I had no time to try this wine, which along with Žilavka received medals from “Decanter.” Afterwards I got a drive to the center and my wine trip to Trebinje was basically finished, my bag full of notes, my head full of memories.

Trebinje seems to be an exceptional piece of earth, hot and dry, but giving balanced and elegant wines, although usually quite heavy and rich. Beautiful as a town, close to such touristic attractions like Dubrovnik, Mostar and Kotor, it surely deserves more attention… especially from wine lovers.

small farmers’ market

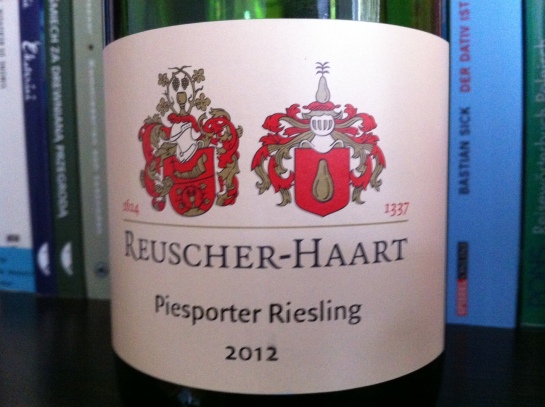

This romantic description refers to the valley of Moselle, in German Mosel, after which the wine region is named. Mosel, possibly the best known (and still too little!) German wine region, stretches from the border with Luxembourg to the city of Koblenz, where Moselle flows into the Rhine.

This romantic description refers to the valley of Moselle, in German Mosel, after which the wine region is named. Mosel, possibly the best known (and still too little!) German wine region, stretches from the border with Luxembourg to the city of Koblenz, where Moselle flows into the Rhine. Here, like in many other parts of Germany, the dominating variety is Riesling, which once ennobled the local wine making. Up to the end of 19th century, some of the Mosel Rieslings enjoyed fame comparable with celebrated Bordeaux reds. The two devastating World Wars and following developments resulted in a decline in quality and so Germany started to be associated with easy-going semi-sweet whites like Blue Nun. From the 1980s on, this has almost ruined its reputation as consumer preferences shifted. Since then the quality dramatically improved and the valley of Mosel offers us again some of the most splendid white wines in the world. Though, prices remain relatively low and a great value for money is what results from this – surely not long lasting – situation.

Here, like in many other parts of Germany, the dominating variety is Riesling, which once ennobled the local wine making. Up to the end of 19th century, some of the Mosel Rieslings enjoyed fame comparable with celebrated Bordeaux reds. The two devastating World Wars and following developments resulted in a decline in quality and so Germany started to be associated with easy-going semi-sweet whites like Blue Nun. From the 1980s on, this has almost ruined its reputation as consumer preferences shifted. Since then the quality dramatically improved and the valley of Mosel offers us again some of the most splendid white wines in the world. Though, prices remain relatively low and a great value for money is what results from this – surely not long lasting – situation. Last summer, I had an opportunity to try several of Martin Müllen’s wines and, dear me, there was not even one I disliked or found mediocre. It is also incredible what a great aging potential Riesling might have! I fell for 2008 Trarbacher Hühnerberg Riesling’s charm, a dry masterpiece of a lovely opulence, balanced acidity and light black currant notes (!), which are going to become more intense with time. Unforgettable were all Late Harvest wines (German: Spätlese): the 2012 Kröver Paradies, which was defined as fruchtsüß, that is fruity-sweet, and elegantly united the delicate sweetness with freshness; the 2012 Trarbacher Hühnerberg Riesling Spätlese – a feinherb (≈ off-dry) creation reminding of candy and matching red meat or game, a result of long pressing process (decent tannins from skins) and maturation in wood; and the 2005 Trabener Würzgarten Riesling Spätlese – another masterpiece uniting sweetness and acidity, containing distinct black currant notes, so seductive! The last Late Harvest beauty was the feinherb 2011 Kröver Letterlay Riesling Spätlese, which proved to be truly vigorous and as such was paired with roe venison goulash and spätzle with Mirabelle plums. The long degustation (I have not named even a half of the wines) finished with 2003 Kröver Paradies Riesling Auslese “Abbi,” served together with plum strudel. The 2003 vintage offered at the Mosel overripe grapes, which produced wine perfect for long aging. This one was creamy, dominated by the aroma of ripe strawberries, and manifested smart noble rot character.

Last summer, I had an opportunity to try several of Martin Müllen’s wines and, dear me, there was not even one I disliked or found mediocre. It is also incredible what a great aging potential Riesling might have! I fell for 2008 Trarbacher Hühnerberg Riesling’s charm, a dry masterpiece of a lovely opulence, balanced acidity and light black currant notes (!), which are going to become more intense with time. Unforgettable were all Late Harvest wines (German: Spätlese): the 2012 Kröver Paradies, which was defined as fruchtsüß, that is fruity-sweet, and elegantly united the delicate sweetness with freshness; the 2012 Trarbacher Hühnerberg Riesling Spätlese – a feinherb (≈ off-dry) creation reminding of candy and matching red meat or game, a result of long pressing process (decent tannins from skins) and maturation in wood; and the 2005 Trabener Würzgarten Riesling Spätlese – another masterpiece uniting sweetness and acidity, containing distinct black currant notes, so seductive! The last Late Harvest beauty was the feinherb 2011 Kröver Letterlay Riesling Spätlese, which proved to be truly vigorous and as such was paired with roe venison goulash and spätzle with Mirabelle plums. The long degustation (I have not named even a half of the wines) finished with 2003 Kröver Paradies Riesling Auslese “Abbi,” served together with plum strudel. The 2003 vintage offered at the Mosel overripe grapes, which produced wine perfect for long aging. This one was creamy, dominated by the aroma of ripe strawberries, and manifested smart noble rot character.